Masha Slepak was, along with her husband, a central figure among the Moscow refuseniks of the 1970s, Colin Shindler wrote in The Jewish Chronicle on 15 September.

Last Sunday Masha Slepak was buried in Jerusalem’s Har HaMenuchot cemetery alongside her husband, Vladimir. For virtually the entire duration of the Soviet Jewry campaign in the UK, they were the central figures among the Moscow refuseniks. For Jewish “tourists” to the USSR, their apartment on Moscow’s Gorky Street was a fixed destination.

Masha’s name is always indelibly linked with that of her husband, but she played a full role in the refusenik movement in signing collective letters and taking part in protests.

Yet often women activists had the added task of keeping family and home together. They had to keep calm and carry on despite the repeated arrests of their husbands, the searches of their homes and the harassment of their children. They were strongly supported by countless thousands of women in this country.

Masha was born Mariya Rashkovskaya into an assimilated Jewish family in 1926. She graduated from a Moscow medical institute in 1951, met and married Slepak, a specialist in radio electronics shortly afterwards.

This period of their early married life, Stalin’s last years, was characterised by a vehement antisemitism. Masha’s father-in-law was a loyal Old Bolshevik who named his son after Vladimir Lenin and his daughter after Rosa Luxemburg. He justified both the Nazi-Soviet Pact (1939) and the Doctors’ Plot (1953) in which mainly Jewish doctors were accused of poisoning the Kremlin leadership.

This event provided the first stirrings in Masha’s mind that something was not quite right in the land of communist pioneers. Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War changed her perception of herself forever.

Although the Soviet Union cut its diplomatic ties with Israel during the war, it began to allow emigration again in August 1968. The Slepaks decided to leave and became involved in the first collective activities of the refuseniks. They were given the task of photocopying copies of the first Zionist periodical, Iton, compiled in Riga and distributed throughout the USSR to sympathisers.

Masha, her husband and their two sons Leonid and Sanya, first applied to leave in April 1970.

They were finally informed on October 14 1987 that they could emigrate. The years in between were ones of frustration and despair, resilience and stubbornness. They were determined not to give in, not to give up.

At the end of 1972, Masha and Vladimir were told by a Soviet official: “It is in the interests of the State not to let your family out now. When it will be in the interests of the Soviet State, then you will be let out. Perhaps you will be let out next year, perhaps in two years, perhaps even this year. I might add, perhaps never… the same concerns your sons.”

In 1975, they decided that it would be best for Masha and their sons to try to leave separately as Leonid was due to be conscripted into the army in 1976. They decided to divorce to facilitate this plan. They were refused once more. Andrei Verein, the head of the Moscow visa office said they should count themselves lucky — “Twenty years ago we would have shot you”.

British support came in the form of weekly telephone calls from the then Labour MP Greville Janner and his wife Myra, who were prominent in the UK Soviet Jewry campaign. One hundred and seventy MPs signed a siddur for Leonid’s barmitzvah, and Masha’s mother paid a visit to Britain where she was greeted by campaigners.

In 1977 the elder son, Sanya was allowed to leave. In 1979, Leonid who had “disappeared” to avoid conscription was also granted an exit visa.

In between, the Slepaks and other leading refuseniks became the targets of renewed oppression.

On June 1 1978, Masha draped a banner over the balcony of the family’s apartment which read: “Let us go to our son in Israel”.

This demonstration touched a raw nerve. A hostile crowd gathered below and cauldrons of scalding water cascaded from above.

The protest earned Vladimir five years exile in the remote village of Tsokto-Khangil, 3,000 miles from Moscow, on a charge of “malicious hooliganism”.

Masha was given a three year suspended sentence but joined him in exile. On returning to Moscow in December 1982, Vladimir gained employment as a lift operator while Masha was unemployed.

Before his death in 2015, Vladimir revealed he had been the only non-party member of a state commission for selecting the USSR’s anti-aircraft and anti-missile defence systems. This probably formed part of the rationale for the continual visa rejection, but it did not explain the refusal of other activists who did not hold such high-level security positions.

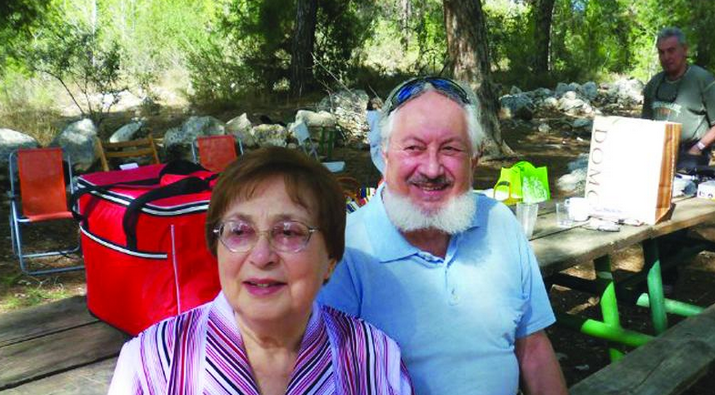

After finally leaving the USSR, the Slepaks lived quietly in Kfar Saba and spent their last years cared for by their sons in New York.

A poster depicting the Slepaks at demonstrations often included the slogan: If you turn your eyes from us, even for a moment, we will cease to exist.

In this country and others, eyes were not turned away during those 17 years. On a daily basis, ordinary British Jews were remarkable in their work for the Slepaks and their comrades.

Dostoyevsky asked “What makes a hero? Courage, strength, morality, withstanding adversity?” Yes — and more — as the Slepaks demonstrated to all of us.

Colin Shindler is a historian who worked for the UK campaign for Soviet Jewry between 1966 and 1975